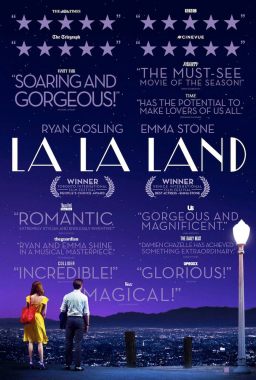

Dir. Damien Chazelle (Lionsgate, 2016)

Conflict and compromise. This, we learn from Damien Chazelle’s La La Land (2016), is what governs jazz, as well as, presumably, love, life, the universe, the TV remote, and everything. We begin on a jammed LA overpass in the baking heat, with anything that could possibly stifle a body and soul set to high. What breath of fresh air might release these pent-up, pining spirits, I hear you ask? Why, dance, of course! And song! The opening number, with its cornball Gap-ad/Glee-style rainbow harmony and apparent absence of satire, had me eyeballing the exit, seeming at best well-intentioned naivety put through its paces, and at worst a clumsy backfire in the handling of an art form’s racial politics (a bit like the jazz theme, in fact). The film’s poster has been hijacked several times in recent weeks to lambast Brexit negotiations, another form of spirit-breaking gridlock in which nostalgic fantasy and cultural reductionism have been crushed uncomfortably together. We are perhaps primed, then, to read a wilful, even predictably dutiful, trip to the 1950s via the Disney Channel in the hot mess we are given for starters.

We’ve been here before, in any case, the heat of the city stirring unruly passions à la West Side Story, though real conflict drove the movement there, and the energies here seem vapid in contrast. We worry this will carry over into the first meeting of our leading lovers, Mia (Emma Stone), a heart-of-gold actress-cum-barista-cum-dreamer – filmic shorthand for loser – who wants to get off of Hollywood’s parching freeways and onto its sunlit uplands, and Sebastian (Ryan Gosling), a heart-of-coolest-ice asshole who wants to recede into Hollywood’s darkest, speakeasiest corners and dedicate himself to the white man’s burden of reviving trad jazz. We find her conning a speech for a part we are given to understand, from her loser’s flustered manner, that she will never get. He honks at her to move, she flips him the bird, they hate each other, and the stage is set for compromise.

We follow Sebastian to the lame-o club at which he works, playing Christmas carols on a piano at the strict command of his lame-o boss (J. K. Simmons), while his fingers burn and itch for jazz. He toes the line till he can hold it no longer, lets his hands go with some show-stopping wonderfulness, and gets fired for his troubles. In walks a downtrodden Mia – who didn’t get the part – drawn by his siren song; she tries to say hello and gets barged aside for her troubles, not so much by a disappointed man as a walking commitment to caricatured cool. We’ve had plenty of this kind of retro-fit LA fakery before, in Swingers, for example, with its pomaded lindy hoppers swarming the bars of the 1990s, making themselves up from the clutter of a romanticised past. Who wouldn’t want that? So, she keeps at it, and, through a series of encounters that get less hostile and awkward by degrees, chips away at his posturing aloofness till the real him starts to show. But why bother? Well, the fact that he’s Ryan Gosling can’t hurt – you would, wouldn’t you? – a bona fide, modern-day-classical leading man, and Emma Stone has the strange beauty, the comic chops, and the plausible kindliness to make anyone drop their guard. Even him, naturally.

So far, so conventional, but from the opening sequence a couple of smart little rips have appeared in the space-time fabric of this world to disturb the sense that we are buying into it solely at face value. It is, we learn, winter, in spite of it clearly being too darn hot, and the minutely subtle lean towards the multi-dimensional starts to calibrate and confirm layers of reality beyond the bounds of traditional musical movie rules. Also, while she is practising lines in her car, he is wrestling needlessly with the rewind function of a tape deck in his, despite it being 2016 – though the recent rash of vinyl sales may yet make this a moment of keen prescience – seemingly to assert his nostalgia as an ascetic choice, necessary to living. Indeed, it’s what he wants to do for a living. The film repeatedly ditches technology when it’s going for emotional purity. He waits outside a movie theatre for her and wonders where she could be, and she writes her play on a piece of paper, while at other times care is taken to emphasise iPhones and emails as the way most of us talk. The moment where she puts her car keys to her head on his advice to strengthen their signal – despite the fact ‘it gives you cancer’ – is another nice reminder that the most potent transmitter of energy out there is still us.

It’s at this point that they start to move, and the first dance, in which they figure out the new laws of attraction and of physics that their universe has taken on, is a joy to behold. But here’s the thing: if it seems like whimsy, it nonetheless stumbles around with the unsteadiness of improvisation, one sole of lead set firmly on the earth, and while most musicals present the song-and-dance number as something both intrinsic and polished, this one seems to know while it’s happening that it’s all a shaky dream from which we will need, at some point, to wake up.

Mia’s and Sebastian’s are nimble souls, though, and their lives are built almost wholly upon robust dreams. It is, then, to the audition room that she takes hers to be crushed beneath a jackboot, skilfully and sincerely baring her soul to people who don’t deserve to see it. Even a readable facial expression in return is considered too much effort, though Chazelle does well to not trivialise this, and the distinct textures of her personhood, as well as her pain, can be felt through this institutional drive to homogenise and reject. She wants what everyone wants and he wants what no one wants. Hers is a living art nobody wants to see and his is a dead art nobody wants to hear. So, what to do? Push back at reality until it bends and shapes itself to your creative wishes, that’s what. Their very decision to dance here is an act of resistance, and an artful contrivance for the resurrection of a dead art form, the minor miracle that the film itself manages to pull off.

The last time this was done with so much care was surely Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist (2011), and if that film taught us anything it’s that old Hollywood, behind the magic, was never that nice anyway, turning its back on all of its darlings sooner or later. For Mia and Seb (the possessive form of which she suggests as the moniker for his dream club), the world’s rejection is the thing that binds them. Well, that and love. Genuine, crazy, glorious, float-away-on-the-air, dance-among-the-stars love; go-to-old-cinemas and walk-among-monuments and sing-like-you-mean-it love. And it is genuine, and crazy, and glorious, and amateurish, and freeing, and renders us special in the power it puts in our hearts and our feet to feel and move and dream and be kind and hopeful and honest and make the most of our fleeting lives. Well, that’s what we’d like. What we get, on the other hand, can be another matter entirely.

The second act is a more dour affair, the closed-down theatre where he’d taken her to see Rebel Without a Cause a deft, melancholy hint that we’re shifting into a minor key. It recalls, in a way, Manhattan, another cinematic hymn to a city and a filmmaking style, where each emotional mark remains unhit and a world of missed chances pervades. He starts to find some success on the road, they drift apart and argue, she writes a play which nobody – except her roommates and a couple of sneering jerks – comes to see, and he of course misses the simultaneous opening/closing night for what proves a degrading photo-shoot with his band. She leaves him, and LA, in tears and in defeat, though unbeknown to her or us, the V-est of VIP movie producers (well, it is a Hollywood fairy tale) was there that night. The scary godmother calls for Mia, gets Sebastian, and he drives out to her small Nevada town to tell her he believes in her and that she needs to audition, knowing in his heart she’ll get to go to the ball, and forget about her piano-playing pauper in the world of Prince Charmings that awaits. She goes, bursts into song – ‘Here’s to the hearts that ache, Here’s to the mess we make’ – knocks it out of the park, and awaits the news that we all know is coming. They say they’ll always love each other, at the bench where they first learned to dance, and they mean it, oh, how they mean it, and we succumb to the inevitable flash forward, and the hand-held claustrophobia and shot aspirations of the middle section give way to the successes of five years later and to rich CinemaScope. And to something wonderful that I wasn’t expecting.

Into his club, ‘Seb’s’, with her movie-star husband, walks a distinctly un-downtrodden Mia, who did, and will now always, get the part, and onto the stage walks the man himself. He plays the show-stopping wonderfulness that first drew her to him, her face falls, the lights fade, a dolly shot approaches, and we are whisked into a fantasy flashback of everything we have seen replayed in an alternate universe, starting with him dropping every pretence to cool and just kissing her. Here they don’t need to falter through dances because the timing is perfect, and each number drenched in sumptuous colour and confident movement and sweeping crane shots, the paean to old Hollywood that we all came to see. But the technical achievement of the sequence is to conjure not so much a world in which we are able to sing and dance at will, as one in which we are able simply to act.

In this regard, the enterprise at large seems less a panting homage to LA or to old-time films as it is a steady homage to people, which is perhaps ultimately what movies ought to be. This is the city of cinematic dreams, though they are worth next to nothing if they don’t draw from the well of what’s best in us all. The paradox of movies, and musicals in particular, is that they are fundamentally dishonest about the forms of human relationships, while managing at the same time to honour them very well through the organising principle of choreographed flailing. For we stumble around, aiming at the right steps, taking each other to movies, plays, galleries, operas, recommending books and wines and learning to play instruments and thinking of funny and clever things to say – or, indeed, write – in the hope it will make other people love us, especially if we don’t let them get close enough to see through us in the first place. But you can’t dance without getting close. It’s part of the deal – cooperation, conflict in harmony, what Shakespeare might have called the strong toil of grace, and, like living, it doesn’t come without a measure of effort or pain.

Maybe it would have been better if he’d just kissed her. He wouldn’t own the club if he had; he’d be in the audience, with her, getting out for an evening while their child was at home with a babysitter, and that would be okay, and more than okay, because it would be better, but sometimes we can’t have better, because either through circumstance or our own inability to seize magic moments when they come, we’re forced to make do, and to patch our armour together out of whatever’s around, and to keep going, and sometimes we have to do that on our own, and sometimes that’s because we could have done better for others, and sometimes it’s because we did our best and they still found their way to someone else anyway. Maybe in the end she is the more conventional person, the one meant to have the 2.4 children and the husband and the above-ground career, though his Hoagy Carmichael impression in the smoky bowels of his club reeks of cliché and performed passions. But if we’ve learned one thing here it’s to distrust the impulse to make conventions of people and the way they feel. Relationships are, after all, governed by the unique wishes of two individuals to dance, to fall in love with, and to walk out on each other as the situation demands. The smile they share as she heads out the door one last time is, if nothing else, a moment of compromise to release them both, finally, from conflict. Here’s to the mess we make.